[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”3.22″][et_pb_row _builder_version=”3.25″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”3.25″ custom_padding=”|||” custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.4.7″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” width=”76%” max_width=”76%”]

Author: Jasper Caverly

CW: Sexual assault, violence against Aboriginal people

This essay contains spoilers for The Nightingale (2018)

Subversive media has the ability to undermine dominant rhetoric, hold the arms of societal power to account, and ultimately spark the idea of social change . Cinema’s history, especially, tends to mirror a nation’s mentality; encapsulating the audience’s collective desires, or seeking to challenge them. Films and their inhabitants, then, often reflect a nation’s subconscious, acting as an inadvertent expression of culture, values and ideology.

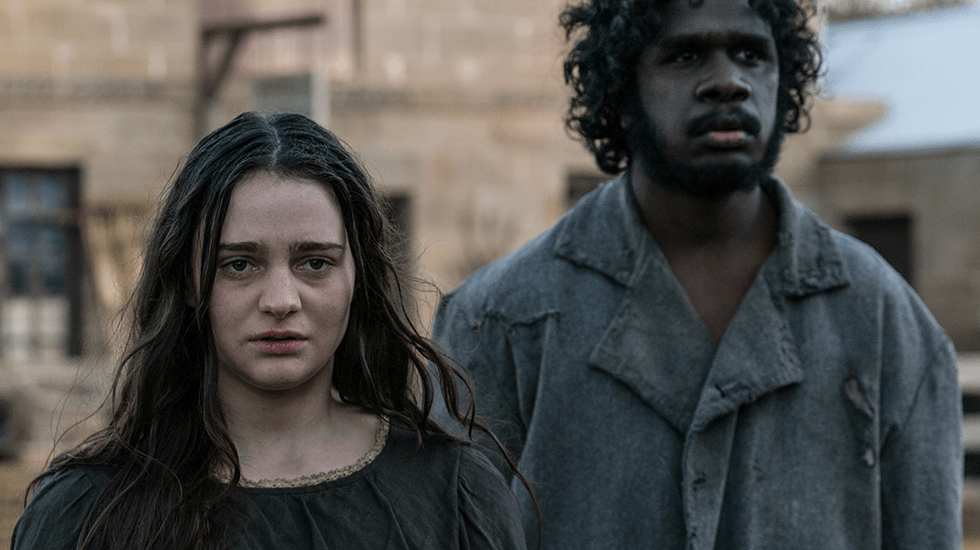

For the purpose of this essay, I am particularly concerned with the characterisation in Jennifer Kent’s Australian psychological thriller The Nightingale (2018) . If we delve deep into Kent’s film, we can begin to understand how cinema can simultaneously represent Australian national archetypes and reflect contemporary societal concerns, while challenging homogenous perspectives of identity.

The Nightingale is set in the colonial frontier of Tasmania, 1825, where British colonists and Indigenous peoples fought over custodianship during the genocidal Black War. Kent’s film uses this context as a backdrop to query identity (and thus power) in the colonial past, consequently providing a commentary on our ‘post-colonial’ present. Hierarchies of class, race, and gender are embodied in the film as persons of the soldiery, conviction, settlement and indigeneity (Harman, 2020 p. 2).

As such, I would like to select two distinctions of characterisation for further discussion within this essay: women (gender) and Aboriginal peoples (race). In keeping with the historical context of The Nightingale, both are shown to exist in opposition to British rule. Although The Nightingale is arguably led by a female protagonist, the world depicted in the film is certainly reigned by the hand of white men. In its earliest years as a colony of the British Empire, Australia was dictated by the monarchy, militarist power and norms of patriarchy.

This is reflected strongly and often cruelly in The Nightingale. Protagonist Clare, an Irish convict and mother, is instantly shown to be at the mercy of soldiery and forced into acts of physical labour. Lieutenant Hawkins, who has the ability to grant her freedom, is unwilling to write her a letter of recommendation as he, being of high-ranking social power, would no longer be protected by law which allows him ownership of her. Hawkins is shown exploiting this power multiple times as he rapes her without consequence, then murders her husband and baby.

Impelled by these atrocities, Clare undergoes a visible transformation that likens her to a ‘Paddy’ – an archetype often represented in conflict to or as a fracture of British identity. McLoone terms the ‘Paddy’ as being “…[a] simian primitive – a violent and irrational character who came to represent the Irish as a whole.” (2001, p. 209). This transformation is important, as it places Clare in direct opposition to British military rule, not only by nationality and gender, but nature and motive. Although she is a colonist herself, Clare becomes the narrative instigator, whose purpose is abject to the other colonists. While she desires freedom from her life of conviction, the colonists seek to manifest the land unto the monarch’s will. There is a dichotomy of aspirations here, and on the part of the audience, a psychological attraction to the disadvantaged.

As spectators, we then compel Clare to exceed the contextual expectations of the world she inhabits and fulfil her need for retribution in the form of violent justice. The efficacy of Clare’s emblematic defiance is best described by Curthoys, who writes, “Through contested allegorical images of the convict woman, national history is made and remade in moral, economic, and cultural terms, implying the eternally recurrent question: Is Australian history a cause for shame or pride?” (2003, p. 81).

Another distinction of identity explored in The Nightingale is the relationship between Indigenous and colonising Australians. Before I unpack this relationship, however, it is essential to underscore the notion that Australian films operate within the context of documented genocide, beginning in the 18th century, whereby the custodians of the land have been (and are being) dispossessed by British settlers. Public interest, factual scrutiny and exploration of the Indigenous/settler relationship in media demonstrates that the ideation of ‘Australianness’ and what it means ‘to be Australian’ are salient, if not central, to a national sense of identity (Walter, 2012 p. 15).

In Kent’s film, ‘Billy’ (whose name is actually Mangana), is a Letteremairrener man who has experienced white assimilation and slavery and is therefore able to speak english (Screen Australia, 2018). Billy is employed to help Clare pursue Hawkins across the unconquered bush of ‘Van Diemen’s Land’, a task which would be impossible to navigate without navigation and a means of surviving off of the land – knowledge Billy has collected through his upbringing. What Billy represents is a recurring archetype of Indigenous characters in Australian cinema: ‘the tracker’.

The tracker entered Australian mythology (and cinema) as an Aboriginal with uncanny powers of observation, integral to nation-building, but one who is mostly a voiceless participant in dialogue between coloniser and pre/colonised spaces (Langton, 2006). However, Billy’s character in The Nightingale is portrayed with agency, rendering him exempt from pre-established stereotypes. He is written to be resourceful, intelligent and compassionate, even in the face of cultural extermination. Essentially, Billy embodies Indigenous oppression within the narrative and its historic context, by acting as a voice for voiceless participants – one that serves to celebrate Aboriginality, rather than exploiting it.

The creation of Billy’s character was closely supervised by Jim Everett, from the plangermairreenner (sic) clan of the Ben Lomond people, who acted as a cultural consultant and associate producer on the film. This level of cultural consultation was crucial for the production team to create a character who effectively embodied the dispossession, violence and enslavement endured by Indigenous Tasmanians. Arrow & Findlay write, “The film is also replete with images and evidence of Indigenous survival and resistance…Billy’s final line in the film – ‘I’m still here’ – is a defiant declaration of survival in the face of unbreakable sadness. Here Billy speaks from the past to the audience in the present.” (2020, p. 3).

Today, Australia is made up of a broad, cosmopolitan population; the result of 250 years of foreign settlement and globalisation. Despite the country’s apparent embrace of multiculturalism, the typified Australian identity remains the masculine, hard-working, fair-go bloke from the outback (or interchangeably, the frontier). Attitudes of nationalism determine that the ‘average’ Australian speaks english, respects political and judicial systems, and is garnered by a cognitive sense of ‘feeling’ that they belong here (Healey, 2016 p. 27). It is through these aspects that Australia’s colonial past remains victorious, supported by the book-keeping of national history and educational curriculums – a systemic hegemony granting ignorance to the lasting effects of colonialism and quelling settlement anxieties.

The Nightingale is ultimately concerned with the unification of minority groups and allyship in the face of adversity – solidarity in a disharmonious social climate . It seeks to hold ruling powers accountable for their past and present by disrupting the possibility of an inequitable future. It opposes notions of supremacy by representing two of the many identities that have been historically discriminated against, disadvantaged and disenfranchised by hierarchical malice; a malevolence decided on the basis of gender, race and class.

The way Kent’s film engages with characterisation should be seen allegorically; as retaining social pertinence in contemporary dialogue, and challenging the ‘victory’ of settlement by subverting the imperial/empirical narrative. Even then, Clare’s victory feels as though it’s worth more than Billy’s. In fact, neither character is genuinely victorious by film’s end, indicating that The Nightingale is closer to a social study of Australia’s sustained, problematic attitudes, rather than a historic one.

Jasper Caverly can be contacted via email: caverlyjasper@gmail.com

Header image courtesy of X-Press Magazine

REFERENCES

Arrow, M & Findlay, J. (2020). A critical introduction to the nightingale: Gender, race and troubled histories on screen,Studies in Australasian Cinema.

Curthoys, A. (1999). Expulsion, exodus and exile in white australian historical mythology, Journal of Australian Studies, 23(61), 1-19.

Harman, K. E. (2020) Uncanny parallels: Jennifer kent’s the nightingale, violence and the vandemonian past, Studies in Australiasian Cienma, (In Press).

Healey, J. (2016). Multiculturalism and australian identity. The Spinney Press.

Kent, J. (Director). (2018). The nightingale [Film]. Causeway Films.

Langton, M. (2006). Out from the shadows: Marcia langton considers the significance and traces the development of the aboriginal tracker figure in australian film, Meajin, (65)1.

McLoone, M. (2001). Political violence and the myth of atavism. In J. D. Slocum (Eds.), Terrorism, media, liberation (pp. 209-231). Rutgers University Press.

Screen Australia, (2018, September 12). The nightingale wins two awards at venice film festival, Screen Australia. <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/sa/screen-news/2018/09-12-the-nightingale-wins-two-awards-at-venice>

Walter, M. (2012). Keeping our distance: Non-indegenous/aboriginal relations in australian society. In J. Pietsch & H. Aarons (Eds.), Australia: Identity, fear and governance in the 21st century. ANU Press.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

Leave a Reply